Karl R. Landis

Director of Leadership Development, Lancaster Mennonite Conference

Who among us would claim to be an expert on prayer? We might eventually master other elements of the Christian life, but does anyone ever fully master prayer? Thankfully we are not commanded to master prayer, even though many of us expect ourselves to work toward mastery of any responsibility we are given. We are, however, commanded to pray. We do not have to understand prayer fully to do it. And, as with many aspects of the Christian life, obedience releases greater understanding. Not complete understanding, but greater understanding.

Who among us would claim to be an expert on prayer? We might eventually master other elements of the Christian life, but does anyone ever fully master prayer? Thankfully we are not commanded to master prayer, even though many of us expect ourselves to work toward mastery of any responsibility we are given. We are, however, commanded to pray. We do not have to understand prayer fully to do it. And, as with many aspects of the Christian life, obedience releases greater understanding. Not complete understanding, but greater understanding.

Over the years, my diligence in prayer has risen and fallen. As a less urgent part of my schedule, my time in prayer has been squeezed by changes in family schedules, changes in work schedules, too much television and too many other commitments. And yet I have also grown in my understanding and experience of prayer. Here is some of what I have learned from my own experience and reflection and from listening to other believers reflect on their experiences.

Prayer brings us to the crossroads of the mystery of God and the mystery of human nature. When we pray, we are confronted with the contrast between our ability to achieve and accomplish amazing things and our inability to achieve or accomplish all that ought to be done or our inclination to use our abilities in wrong ways. We are confronted by our being created in the image of God along with the knowledge that God’s power and wisdom and creativity exceed our own to an almost infinite degree. We are confronted with the paradox of Almighty God’s goodness and grace wrestling with evil and darkness and with human free will. These confrontations take place and work themselves out in each of our souls, providing each of us with the opportunity to declare our allegiance, to choose whom we will serve and to thereby shape the kind of people we will become.

Effective prayer grows from regular rhythms of prayer. One of my clearest memories of studying Greek in seminary was the importance of regular (daily is ideal) repetition and review of what we were learning. After ten or twelve weeks, I was amazed at how much I had learned and how elementary the lessons of the first few weeks had become. I could rattle off by memory Greek words and forms that had initially seemed completely random. As I studied for the final exam, I realized that it would have been impossible to do this preparation by cramming all the memorization and practice into one week my brain simply could not have absorbed that much material and interconnectedness in a single dose. It worked much better to develop my understanding piece by piece over an extended period of time. Unfortunately, now that I no longer repeat and review what I learned, it has faded.

I see a lot of parallels to my prayer life in my study of Greek. When I have prayed in a focused way on a very regular or daily basis, I am usually much more aware of God’s activity around me and of his word. I am usually more peaceful about my circumstances and have a clearer idea of how to proceed. But when I have neglected to pray, I become restless, frustrated and more easily confused. I wonder why God seems so silent.

On the other hand, prayer does not follow a formula like the repetition of Greek grammar. Regular, focused prayer does not guarantee permanent or instant peace with God, although it does seem to make it more likely. All I know is that, just like trying to cram Greek the night before the final, trying to “cram prayer” in a moment of crisis is far less effective in building my relationship with God and cultivating an understanding of how God is providing for me.

Our daily choices shape us. A.W. Tozer said we are all as close to God as we want to be. C.S. Lewis once noted that our circumstances are mostly the accumulation of the thousands of small choices we make in our day-to-day lives. Maturity takes shape one interaction and one experience at a time. Making time for prayer on a regular (ideally daily) basis will shape our intimacy with God, our vocabulary and our imagination. Without prayer, we are likely to be and to feel overloaded, driven and perhaps anxious. With prayer, we may still be busy, but we will enjoy a calmer inner life that is centered on the truth and presence of God in our lives.

Regular prayer connects us to Sabbath rhythms. A daily rhythm of prayer teaches us on a smaller scale many of the same lessons we learn from a weekly day of rest. Both practices remind us of our dependence on God and of the limits of our own abilities. They highlight our hunger for distractions from God that come in many forms, including work, entertainment, possessions, and activities. Philip Yancey points out that Jesus’ recorded prayers were generally focused far more on aligning his will with God’s will than on changing his circumstances.

Maturity leads to greater dependence rather than greater independence. One of the paradoxes we face as Christians is that maturity seems to work backwards in the kingdom of God. In the natural order we see independence as an important part of maturity. A mature person is someone who has acquired enough knowledge, skill or experience to know how to proceed with minimal help from other people. The problem is that we will never acquire enough knowledge, skill or experience to proceed without God’s help and power. The depth of our maturity as Christians is directly linked to our awareness of this truth.

Christian peace comes in part from our willingness to relax into God’s care and provision rather than anxiously using or defending our own abilities and insights. Just like our cat settles in on my daughter’s lap, curling up her tail and closing her eyes, so we can settle in prayer into the providence of God, the lordship of Jesus Christ and the power and presence of the Holy Spirit.

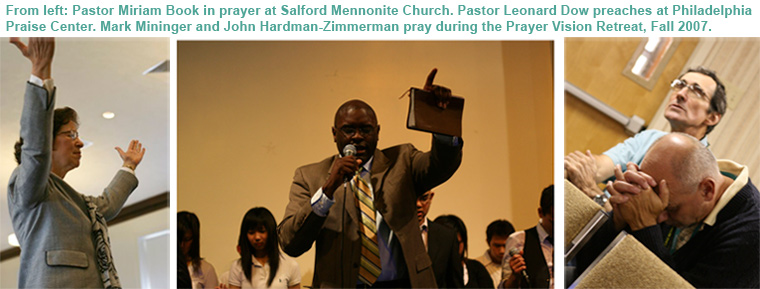

In that same vein, this past week, a group of intercessors from the Souderton area traveled to northern New Jersey for a monthly prayer gathering at Garden Chapel Mennonite Church. As we worshiped, listened to God and prayed together, God strengthened our bonds as our eyes were opened to the work God is doing in that community. Now this team of intercessors prays in a new way for Garden Chapel, a small church at the bottom of a hill surrounded by a busy community. Having actually spent time physically with the congregation gives us a new insight as we pray.

In that same vein, this past week, a group of intercessors from the Souderton area traveled to northern New Jersey for a monthly prayer gathering at Garden Chapel Mennonite Church. As we worshiped, listened to God and prayed together, God strengthened our bonds as our eyes were opened to the work God is doing in that community. Now this team of intercessors prays in a new way for Garden Chapel, a small church at the bottom of a hill surrounded by a busy community. Having actually spent time physically with the congregation gives us a new insight as we pray. How can we take our prayer ministry to a new level? I would proprose that we need to “go” and pray. While there is power in prayer no matter where we are, praying onsite gives us new understanding and insight as we pray. Prayer-walking in your community gives a better look at the demographics, the needs, the strengths. Traveling to visit a missionary or church planter will help you to pray with pictures of the situation, the physical surroundings or needs. Going to visit someone in a hospital will help you to pray with compassion as you sense the pain and suffering they are feeling firsthand.

How can we take our prayer ministry to a new level? I would proprose that we need to “go” and pray. While there is power in prayer no matter where we are, praying onsite gives us new understanding and insight as we pray. Prayer-walking in your community gives a better look at the demographics, the needs, the strengths. Traveling to visit a missionary or church planter will help you to pray with pictures of the situation, the physical surroundings or needs. Going to visit someone in a hospital will help you to pray with compassion as you sense the pain and suffering they are feeling firsthand.

In my encounter with the contemplative tradition and more recently, by attending Franconia Conference prayer intercessors meetings and hosting an Alpha course at our church (see

In my encounter with the contemplative tradition and more recently, by attending Franconia Conference prayer intercessors meetings and hosting an Alpha course at our church (see