by Stephen Kriss

For my 50th birthday, I traveled to Europe to explore my biological family heritage in Slovakia and my spiritual family history in Switzerland and Germany. I began in the Carpathian Mountains where my great-grandparents had lived, discovering family names in cemeteries and noticing the similarities between the landscape and that of the Alleghenies of Western Pennsylvania, where my family later settled. This journey deepened my sense of connection and left some unanswered questions about my familial story, especially about whether, amid a predominantly Catholic family, I might also have Ashkenazi Jewish roots.

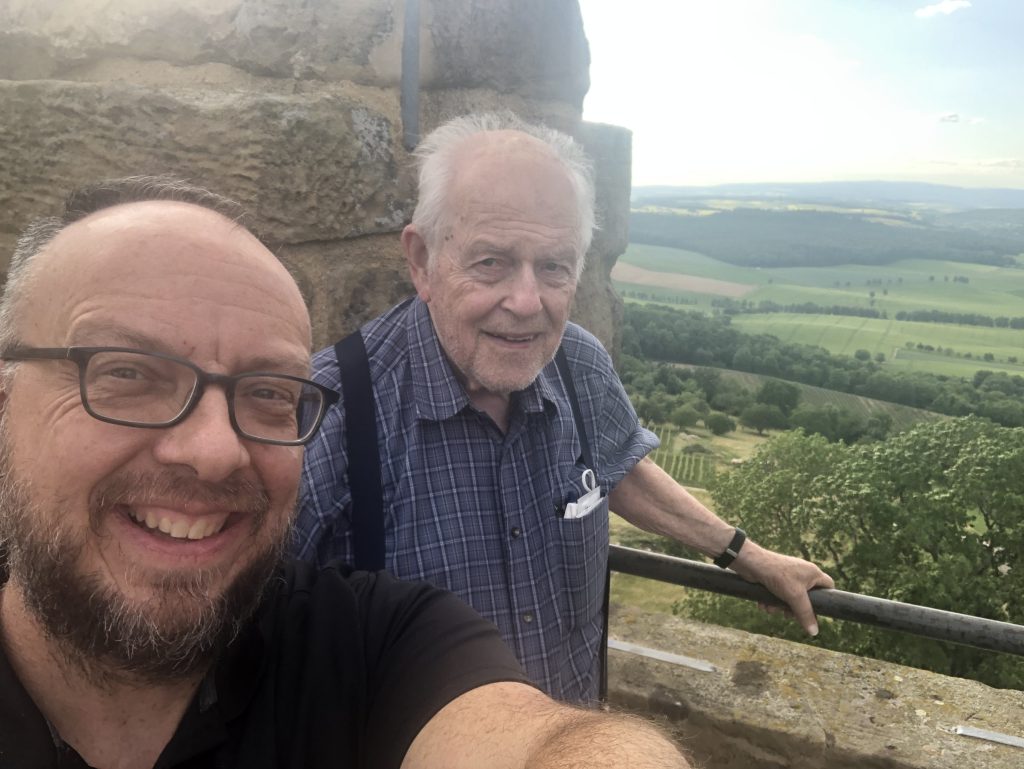

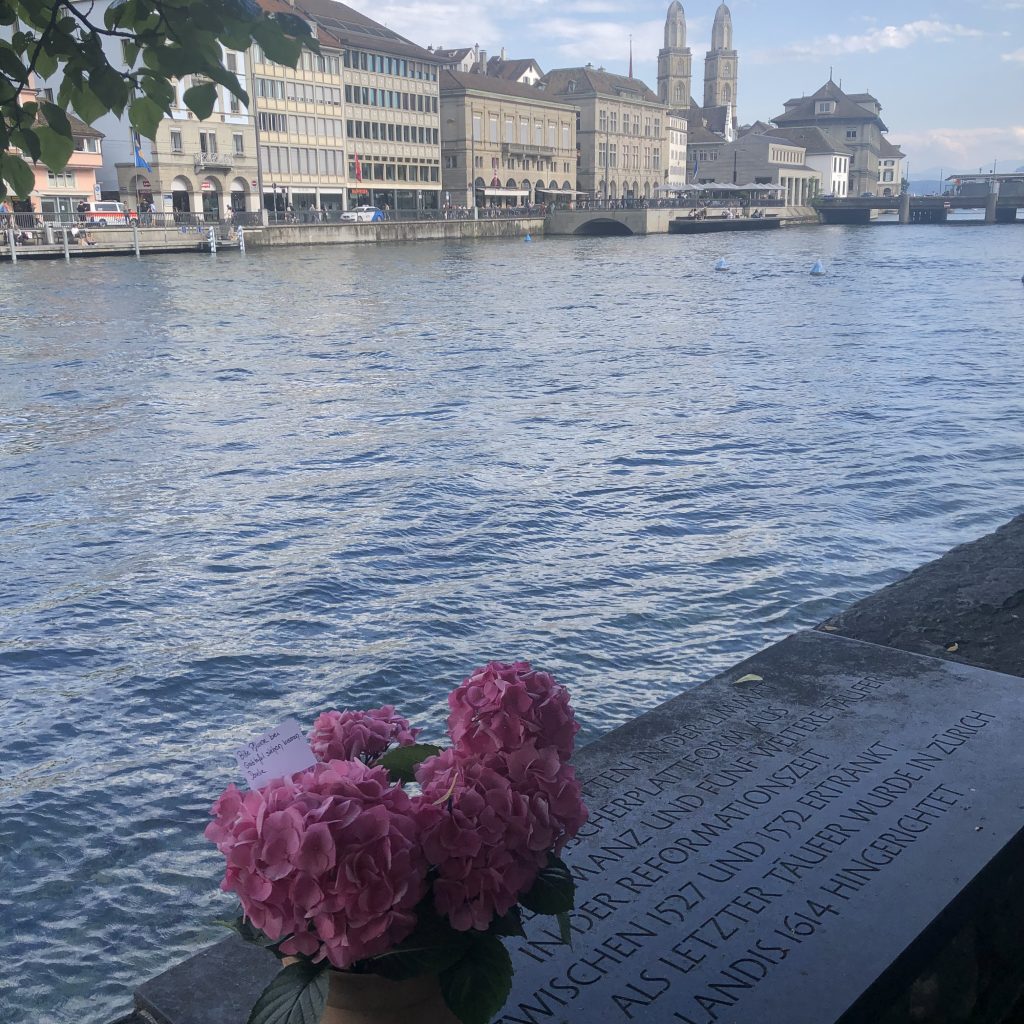

The second part of my trip was a three-day immersion in Anabaptist/Mennonite history with John L. Ruth (Salford [PA] congregation). We visited key locations in Zurich, explored an archive to see a letter written by Conrad Grebel, and traveled to Germany. I saw the family heritage locations for the Landis, Groff, and Alderfer clans who are part of our Mosaic settler families from colonial days. It was a privilege to travel with John, who is now in his 90s, and hear his stories and enthusiasm.

John, his friend Peter Schmid, and I hiked to one of the Anabaptist caves where early members of the movement gathered clandestinely. Peter is part of the movement to stir conversation and confession between Anabaptists and his community, the Swiss Reformed. More than the spiritual significance of the cave, I remember praying together, and Peter gently guiding John as we walked the precarious wooded trail on a rainy morning, possibly the last of John’s many pilgrimages to that spot.

As the 500th Anniversary of Anabaptism approaches next week, I am reflecting on that European pilgrimage trip. Anabaptism was opened to me as a child through a Mennonite church in a mining town in the Allegheny Mountains. I have remained Anabaptist not because of right theology but because of relationships centered in Jesus, in all their brokenness and beauty.

My academic training teaches me to approach belief with humility and openness. I have come to hold my own Anabaptism both lightly and seriously. I acknowledge the beauty and brokenness that exists within the breadth of Christian traditions including our own. I also have experienced that of God in settings beyond the framework of the church.

I recognize that after the heroism of the first generations of Anabaptists, the movement institutionalized, became biologically bound in some settings, and was captive to many of modernity’s traps. I acknowledge that our practiced humility is sometimes the flip side of our arrogance.

This year, as we honor Anabaptism’s beginnings, I am aware that some of us who have been Mennonite all our lives still wonder if it’s our story or how we belong in it. It can be hard to live within and alongside the margins of a 500-year legacy. Sometimes Anabaptism’s exacting and perfecting process can create implicit and explicit boundaries that are difficult to navigate as we seek to faithfully follow Jesus.

Yet I’ve come to know that Anabaptism is always a plurality. It’s localized, contextualized, and personalized. It’s quirky and brave. At its best, it is both deeply personal and fully communal. It’s a balance of the Bible, the people, and the Spirit (though the work of the Spirit has sometimes not been considered enough).

In this time which historian Phyllis Tickle has called another great reformation in the church, Anabaptists have an opportunity to honestly and humbly examine our past and imagine our future. What confessions should we be ready to offer in the midst of our celebration? In what ways does active repentance alter our trajectory? How can we embody the reconciling love of Jesus and exhibit the fruit of the Spirit while interacting with our neighbors in a global and local age?

We will need to again be brave, full of both conviction and humility, repenting from that which has distracted us from the centrality of Jesus. We will need to remain open to the Anabaptisms that continue to emerge, ready to be led by the Spirit into faithfulness and change, binding and loosing, giving and receiving, hoping and working, broken and beautiful.

Stephen Kriss

Stephen Kriss is the Executive Minister of Mosaic Conference.

The opinions expressed in articles posted on Mosaic’s website are those of the author and may not reflect the official policy of Mosaic Conference. Mosaic is a large conference, crossing ethnicities, geographies, generations, theologies, and politics. Each person can only speak for themselves; no one can represent “the conference.” May God give us the grace to hear what the Spirit is speaking to us through people with whom we disagree and the humility and courage to love one another even when those disagreements can’t be bridged.