by Eileen Kinch

Last year, a Friend in my Quaker meeting died. Later I learned that he had named me in his will to take care of his religious books and writings.

Boxes and boxes of old books came to our house, as well as to my parents’. As I sorted through the collection, I discovered a few surprises: a copy of Scottish Quaker Robert Barclay’s Apology from 1678, a two-volume set from 1753 of A Collection of the Sufferings of the People Called Quakers by Joseph Besse, and an almost complete book set of the writings by Quaker founder George Fox.

What does it mean to steward a spiritual legacy? I have spent a lot of time thinking about this. Terry Wallace gave these books to me. But before Terry gave me these books, Lewis and Sarah Potts Benson gave these books to Terry. Lewis and Sarah worked very hard to teach Quakers in the 1970s and 1980s about their religious heritage. Lewis, Sarah, and Terry traveled to Friends meetings in the United Kingdom and in the US with the same message: that Quakers have a very special understanding of Christ being alive here and now, and that we can know and obey him.

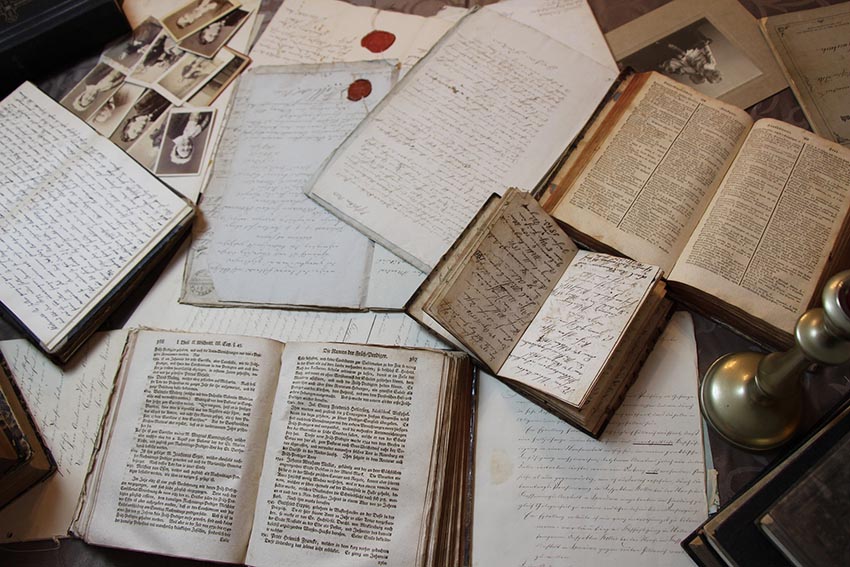

Some of the books have notes scribbled on the edges of pages or even on the end pages. Lewis kept meticulous notes of how Friends used words in their journals or other writings from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. He even assembled a word index. Terry wrote books that interpret some of these older writings. My experience of Christ has been shaped and nurtured because of the faithfulness of others, including Sarah, Lewis, and Terry.

A few Friends recommended that I send older volumes to the archives at Haverford and Swarthmore Colleges. Since Barclay’s Apology is now available online, an archival facility would know best how to take care of a book from 1678. This is helpful advice.

I’m still deciding what I want to do. One thing very clear to me is that the legacy I have been given is not simply the books themselves; what the books contain, teach, or even document is even more important than where I decide to store them. I need to talk and write about my spiritual heritage and why Quaker history and witness are so important. The books are not dead relics. I want them to make a difference for the Kingdom of God, and I want to be a living witness to Christ’s power today.

I am a Quaker who lives and works among Mennonites. Mennonites also have a spiritual legacy that should be nurtured and stewarded. I hope Mennonites are sharing stories of living witness with each other and preserving them at places like the Mennonite Heritage Center. Stories do not simply belong to individuals — they belong to all of us. God’s faithfulness and the faithfulness of our brothers and sisters shape our own.

Eileen Kinch

Eileen Kinch is a writer and editor for the Mosaic communication team. She holds a Master of Divinity degree, with an emphasis in the Ministry of Writing, from Earlham School of Religion. She and her husband, Joel Nofziger, who serves as director of the Mennonite Heritage Center in Harleysville, live near Tylersport, PA. They attend Methacton Mennonite Church. Eileen is also a member of Keystone Fellowship Friends Meeting in Lancaster County.

The opinions expressed in articles posted on Mosaic’s website are those of the author and may not reflect the official policy of Mosaic Conference. Mosaic is a large conference, crossing ethnicities, geographies, generations, theologies, and politics. Each person can only speak for themselves; no one can represent “the conference.” May God give us the grace to hear what the Spirit is speaking to us through people with whom we disagree and the humility and courage to love one another even when those disagreements can’t be bridged.