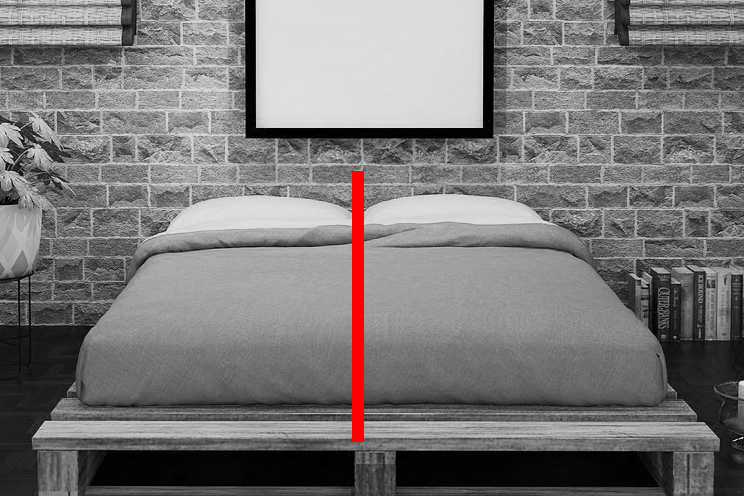

Like many children of my era, I not only shared a bedroom with my older brother, but we slept in the same bed. The promised bunk beds, similar to the promise of chunky peanut butter, never materialized. In our bed, there was a clear, imaginary line down the middle which, if crossed, was fair game for a brotherly punch.

One particular night, we were doing a bit more than our usual messing around. I do not recall the exact details, but there was a loud snap that echoed through our room. We had broken the bed slat at the top of the bed. Living in a small ranch home, we were pretty sure Dad heard the commotion and would soon be appearing in our room.

So, we did what many young men would do … as dad opened the door, our angelic faces rested on our pillows as if we had been sleeping for some time. Dad calmly asked if everything was ok and we quietly said yes. Dad closed the door.

After Dad left, we quickly realized sleep was not going to happen. The problem was our bed was tilted with our heads low and our feet high. As the younger brother, I was instructed to go tell Dad we needed some help. A few bricks solved our problem until the broken slat could be replaced.

This is just one of many experiences in which my Dad’s calm demeanor, in the face of my foolishness, has shaped me. Fortunately, as a result, I find it easy to ask for help. I treasure this as a true gift because I hear from many how hard it is to ask for help, admit need, or worse yet, name personal failure.

Sometimes shame arises from the inability to admit our needs, desires, or failures. I have heard stories while serving at Doylestown Mennonite Church of the creativity, energy, and anxiety people expended to hide their family television from the bishop at one point in their lives. A friend recently told me of a grandparent’s wedding ring that has been hidden in the family since 1922.

I wonder how these experiences have shaped us to keep secrets and to bury our shame. There are layers of shame – as individuals, families, faith communities, and in our institutions. Our larger societal emphasis on public image only adds to this struggle. Often help is within reach, but we remain silent and even proclaim everything is just fine. Ironically, often our struggle is obvious to others … just like my dad knew we needed help with our bed but didn’t offer to help until we asked for it.

I am reminded of the hymn, “The Love of God.” One way to experience the great love described in the hymn is to name one’s needs before God. Sometimes we need to risk our fear of shame when we insist all is fine, while actually trying to sleep uphill on a broken bed. What transformations might happen in our lives, families, churches, and institutions if we begin to trust God with our needs, weaknesses, and failures?

As you rest your head tonight on your pillow, when God asks is everything okay, how will you respond?

The opinions expressed in articles posted on Mosaic’s website are those of the author and may not reflect the official policy of Mosaic Conference. Mosaic is a large conference, crossing ethnicities, geographies, generations, theologies, and politics. Each person can only speak for themselves; no one can represent “the conference.” May God give us the grace to hear what the Spirit is speaking to us through people with whom we disagree and the humility and courage to love one another even when those disagreements can’t be bridged.

This post is also available in: Español (Spanish)

This post is also available in: Español (Spanish)